Queen cells?

In spring, we see many queen cells in our hives, but how can we identify them? Is it the creation of a new swarm? Is it a rescue queen cell or a requeening queen cell?

Worker bees build queen cells to create a new swarm – this is known as natural swarming. Between 2 and 20 queen cells are identified in a hive that is preparing to swarm. This is the natural process of colony division. The old queen will take flight with half the bees, while the other half will take charge of rearing the future queen.

When the queen suddenly disappears, often as a result of mishandling by the beekeeper, the bees find themselves orphaned and have to build queen cells as a matter of urgency. These are built from fasting larvae less than 3 days old, which are fed royal jelly to become queens. In the next few days, a queen will be born from this royal cell. Why are the first three days so important? Quite simply because the larva is fed royal jelly for the first three days, and then this is replaced by a mixture of honey and pollen over the next three days. A queen will be fed royal jelly throughout her growth and adult life. Most of the time, these queen cells are found at the bottom of the frame or on the sides.

What we call a rescue cell is quite simply a queen cell that will hatch before all the others. In this way, the beekeeper can recover the other queen cells that have not yet been opened before this queen takes the opportunity to destroy them.

In autumn, queen cells may also appear in the hive. This is not preparation for swarming, but requeening. What is the difference? The creation of queen cells in the case of requeening is due to the poor laying quality of the current queen (probably too old). For safety’s sake, and to avoid being without a queen over the winter, the bees will change her in the autumn to ensure the colony’s survival until spring. So don’t worry: your bees won’t be leaving the hive, just changing their queen.

And there’s also talk of artificial queen cells? No, it’s not a plastic queen, but rather a queen that has been deliberately reared by the beekeeper. This is done on a rearing frame containing around twenty artificial cells called cupules. In these cups, the beekeeper will graft (remove the larva so that it can be moved without damaging it with a pick) a young larva less than 24 hours old, from a selection colony (which has the desired genetic advantages that he wishes to be preserved). Placed in an orphan hive, the bees will build queen cells on the small cups containing the larva. The rearing cycle is then the same as natural swarming (but controlled by humans)!

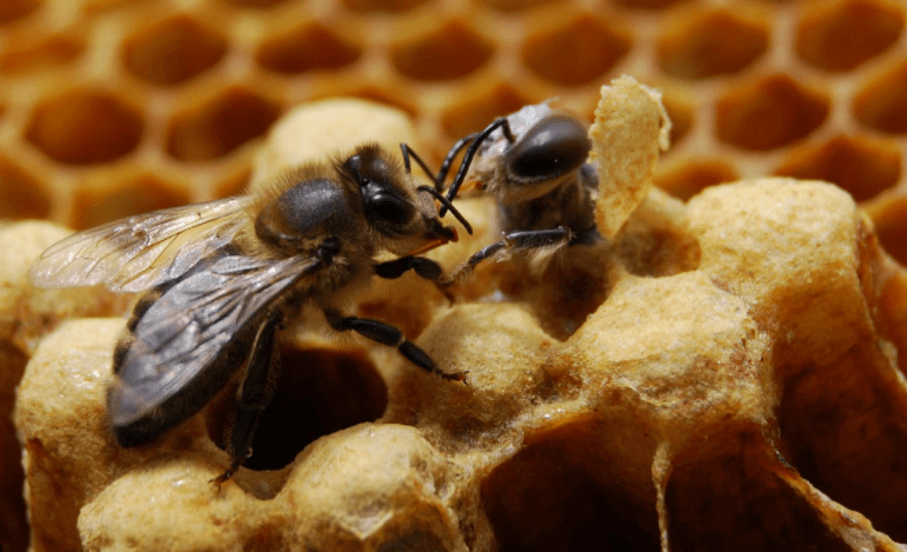

Observation of large alveoli?

Have you noticed large honeycomb-like cells in the brood over the last few days? Don’t panic, it’s normal: these are the males known as drones.

They too are reared in honeycomb cells, but they are larger in size than bees.

The drone is stocky and its thorax is covered in hair. It can also be recognised by its head, topped by two large globular eyes that touch. Its main role in the hive is to pass on its mother’s genetic heritage when the queens are fertilised. However, a male cannot impregnate the queen of his hive (who is his mother). He will go outside to pollinate queens from other hives.

In April, many drones can be seen in the hives, and some frames are even full of them. But more often than not, you’ll find the male cells at the bottom of the brood frames, 5 to 10 cm wide.

The drone has a longer life cycle than the queen and the bee. It begins with the egg stage lasting 3 days. It then weighs 0.16 mg. It then becomes a larva on day 4 and pupates on day 10. The larva can increase in weight by up to 2,200 times, reaching 350 mg on day 13.

It will take a total of 24 days for our drone to be born. On that day, it will weigh between 200 and 230 mg. Yes, it has dropped! The reduction in weight between the larval stage and birth is due to droppings and the construction of the cocoon.

In April, many drones can be seen in the hives, and some frames are even full of them. But more often than not, you’ll find the male cells at the bottom of the brood frames, 5 to 10 cm wide.

The drone has a longer life cycle than the queen and the bee. It begins with the egg stage lasting 3 days. It then weighs 0.16 mg. It then becomes a larva on day 4 and pupates on day 10. The larva can increase in weight by up to 2,200 times, reaching 350 mg on day 13.

The drone’s sexual development begins very early. Sexual maturity is reached between the 10th and 15th day. It will live for around forty days.

The bees eliminate the males at the end of the season. This is because they collect less and less nectar and, as the fertilisation period is over, the drones are expelled from the hive. The workers refuse them access, even stinging them if they are insistent.

As usual, share your photos with us: we’ll post them on our website from the social networks with the hashtag: #apifonda #apiinvert!

See you next month on your API blog with your faithful partner, Les Ruchers De Mathieu!

LES RUCHERS DE MATHIEU Miellerie & Magasin d’Apiculture

Photos ©lesruchersdemathieu