Harvesting honey

The time has come for beekeepers on the plains to harvest the first spring honey made from rapeseed. The nectar from this flower has a high proportion of glucose to fructose, so the honey crystallises relatively quickly. That’s why you shouldn’t take too long to extract it from the frames.

Controlling the moisture content of honey is important! You can do this with a refractometer. This is a tool (also used for wine) that measures the moisture content of the liquid. Your honey should be legally below 20%. Ideally, honey with a moisture content of between 16 and 17% will keep well without fermenting in the jar.

Fermentation of honey can be due to the moisture content, but also to the temperature and length of storage, as well as the type of honey.

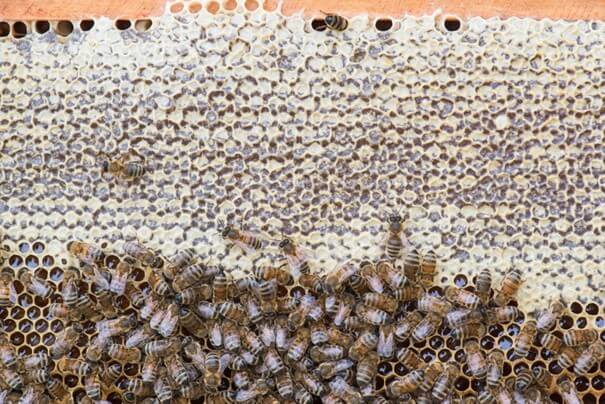

All in all, late April – early May is a good time to take it out of the supers (as soon as the rapeseed has lost its flowers). Of course, the season is not over. Just because you’re harvesting now doesn’t mean you should remove all the supers. If your colony fills one or just a few frames, remove them. Immediately replace them with other empty frames or a new super. For good control of honey conservation, as we have already seen, 80% of the surface area of the frames you are going to remove must be sealed with a wax plug. Otherwise, you run the risk of having honey that is too moist, which could affect its preservation.

How do you harvest frames of honey?

When it’s your first harvest, you may feel a little lost and see this operation as a big job! But rest assured, there’s nothing complicated about it. There are several methods available to you:

1. Harvesting with a brush

You’ll find horsehair or nylon brushes (whatever) in your beekeeping shop. Once your hive is open, remove the first frame from the super as if you were simply observing. Shake this frame 2 or 3 times at the entrance to your hive to make the bees fall in. They will quickly get inside. If you are not using a queen excluder, make sure there is no brood and therefore no queen on it! Don’t knock the frame against the hive either, as this will upset the bees. Once most of the bees have fallen off, take your brush and sweep away the last bees. You need to do this quickly, otherwise you’ll injure the bees by wrapping them in the bristles.

Continue this operation for all the other frames to be harvested. Have an empty frame next to it, placed in a wheelbarrow, to store the frames collected, one after the other. Add a frame cover on top to prevent bees from returning.

2. Harvesting with the bee catcher

The bee catcher is a plastic module attached to a frame cover and used as a funnel. Placed between the body and the hive the night before harvesting, the bees will descend during the night without being able to climb back up, thus freeing the hive. You won’t get as many bees out as with the brush, but you’ll get the job done. Here again, if you have not put a queen excluder in place and there is egg-laying in the brood chamber, the bees are unlikely to leave.

3. The leaf blower

This method may seem crude, but it is widely used by professionals and semi-professionals. The leaf blower allows you to move quickly and avoid upsetting the following hives.

You lift the frame and place it directly on the field without looking at the frames. The head of the frames is facing us to propel the bees by the blast towards the front of the hive. At first sight, a lot of bees fly around the hive, but the mess doesn’t last long. They will all return to the entrance almost immediately.

Be careful with this method if you don’t have a queen excluder! You risk sending the queen flying outside and losing her.

With the blower in hand, you’ll force air between the frames to flush out the bees. In 30 seconds, your hive box will be empty of its occupants. All you have to do is place the frames in your wheelbarrow and place a new, empty hive box on top of the hive before closing it.

To each his own! When you’ve finished harvesting the honey supers, head for the honey house (or your kitchen, doors and windows closed) to extract the honey…

How do you spot flowers?

Bees, like other pollinators, use precise clues to identify the flowers they are visiting. At first sight, this means their colour, their scent… but that’s not all. Researchers have discovered that foraging bees are also sensitive to variations in the temperature of flowers to identify those richest in food.

In a British study published in 2017 in the journal eLife (https://elifesciences.org/articles/31262), we learn that bees and bumblebees are able to perceive variations in temperature between different parts of a flower, known as ‘thermal patterns’.

In this way, they can differentiate between flower species to select those richest in nectar. These temperature variations can be as high as 11°C, and can also occur in common species such as daisies or poppies. Out of 118 species studied, more than half showed temperature variations on the petals.

Pollinating insects sense this difference using thermal detectors on their antennae and legs. In general, these thermal patterns are 4 to 5°C higher than the rest of the flower. This heat is thought to be produced by thermogenesis (the ‘blood of the flower’ heating up) or by daylight.

Global warming is also a threat. Every change in temperature in the environment can have a significant influence on the efficiency of bees as they visit flowers following thermal patterns.

Water collection

Water is an essential nutrient for all living things, including bees. They use it in particular to prepare the ‘larval slurry’, a mixture of honey and pollen to feed the bees.

The colony does not store water in the hive. However, science has shown that some bees store water in their bodies to prevent immediate future needs.

It is the foragers (water-carrying workers) who are responsible for replenishing the water supply as soon as necessary, as in the case of hyperthermia of the brood, i.e. when it reaches a temperature of over 36°C.

As usual, share your photos with us: we’ll post them on our website from the social networks with the hashtag: #apifonda #apiinvert!

See you next month on your API blog with your faithful partner, Les Ruchers De Mathieu!

LES RUCHERS DE MATHIEU

Miellerie & Magasin d’Apiculture

Photos ©lesruchersdemathieu